Ms. Corrine Houston

I but fortunately, Miss Corrine's starting fee, one dollar per month, was just within our means.

but fortunately, Miss Corrine's starting fee, one dollar per month, was just within our means.

The town of Shelbyville, Tennessee, population 12,000, was not exactly a haven for artists in the 1940's. Nevertheless, two artists, both women, became well known and collectible in the late 1940's and ‘50's. One was Mrs. Lizzie Evans, and another was Miss Corrine Houston. Miss Corrine, as we all called her, was an amazing character and became a major influence in my life. When I met her she was, indeed, a master, an aging spinster, an eccentric, little ole, hunch-backed lady and according to her was a great niece of Sam Houston. In better times she had studied art at the Mary Sharpe College in Winchester, Tennessee, under “the great Italian master” who was teaching there. In fact, her grandfather Venable had founded the now defunct school. Her family was well populated with dignity and wealth, including an Ambassador and, of course, Sam Houston.

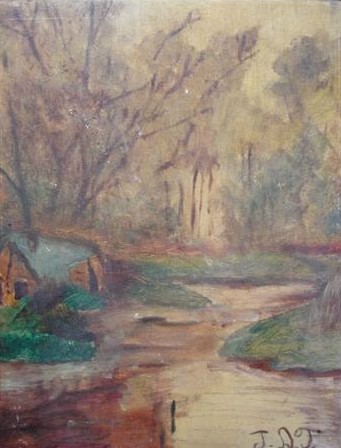

Her paintings looked a lot like those of the English painter, Constable. Anyone who knew her work could spot the style immediately. People who knew her work could look at my paintings and immediately say, “You studied under Miss Corrine, didn't you?”

At Eventide by Corrine Houston, 12X18, oil on cardboard (~1948)

She had painted since she was a child, and had already become a collectible artist because of her classic landscapes. Her classes were a blend of instruction, entertainment, music, and story telling. She told us many stories about her life, some of them over and over. One of her favorites was her beginning work as an artist where she had drawn a figure in the cover pages of a treasured bible that had been a gift to the family from a first cousin of Sam Houston. When her mother began to scold her for her act, her father intervened, stating that he could think of no better place for one to begin a career.

She could trace her family back to the Mayflower and she was quick to run through the generations to prove it. She described a statue of her grandfather Venable located on a college campus somewhere in Tennessee, but I never found it.

She maintained a strong faith in God throughout her life, and even though she was very poor, she kept a charity box on her mantel in which she placed spare change to give to the poor. One of the consequences of her religion was her refusal to paint Jesus Christ, simply because she believed that such a painting would have to be more perfect than possible by any human being.

On my first visit, at the age of seven, to Miss Corrine to sign up for art lessons, I immediately observed her hunch back and ask her about the big “hump' on her back. I had no idea how embarrassing that must have been to my mother, who came with me on the first lesson. Without hesitation, she responded that the hump came from reaching high on a canvas to apply paint, and she demonstrated the movement, showing how her shoulder moved upwards. After that day I never so much as noticed the hunch back again.

In fact, the hunched back was only a starter. She had a very strange arrangement of flesh and scarring around one of her eyes. That, she said, was a scar from a time in which a freak accident had resulted an eight-inch nail penetrating her skull and emerging out the side of her eye.

She lived in the only remaining wing of a family mansion house that had almost burned to the ground when she was a young lady. Soon afterwards everything went wrong for her family, untimely deaths, alcoholism, insanity, and other losses and scandals that left them penniless. I was too young to understand some of the stories I heard about such problems. She was reduced to eking out a living by giving art lessons and whatever charity was available. That did not prevent her from contributing to the church and charity as well. She represented the end of an aristocracy. Her home had no lights or water and she refused offers for improvements from anyone.

Miss Corrine became a tutor, mentor and wonderful friend for me for the next three years. Some of the greatest moments of my childhood were spent sitting with her before an easel. At first, Chiggy and I went together twice a week. She charged a dollar a month until we moved to oils, then the price went up to a dollar a week, because she furnished many of the materials. Every time I would try and give her my dollar, she would say that it was not yet time and refuse it. In fact, we had a hard time paying her, so mother often sent me with canned fruit and baked goods to give her.

Our lessons included 3 or 4 hours of drawing, painting, singing (she played a very nice guitar), philosophy, and some times, mischief. Chiggy would always get hungry after an hour of painting, so Miss Corrine would give us money to cross the street to the store for cookies and sodas. Eventually she encouraged us to come separately because we tended to distract each other, and she encouraged me to come as often as I liked. Since I lived within walking distance from her house, it was easier for me to go, so I began to go more often and many times by myself. She was loving but also stern and demanding. If a painting needed attention and it was getting dark, we continued with a kerosene lantern. It is difficult to imagine how a seven-year-old remained calm sitting in the dark with a hunch backed old lady (that some people thought was crazy) in the remains of an ancient mansion. That no one worried about me walking the mile home in the dark also tells something of times past.

Miss Corrine taught us partly by working with us. She was always busy working on greeting cards and commissions that she took from people who wanted her work. Even though she sold her work for very little, paying the dollar a week represented my limit of affordability, so only years later was I was able to acquire anything of hers, except small sketches and paintings that she gave me as samples. Many years later when blessed with more solvency, I purchased every painting of hers on sale that I was aware of.

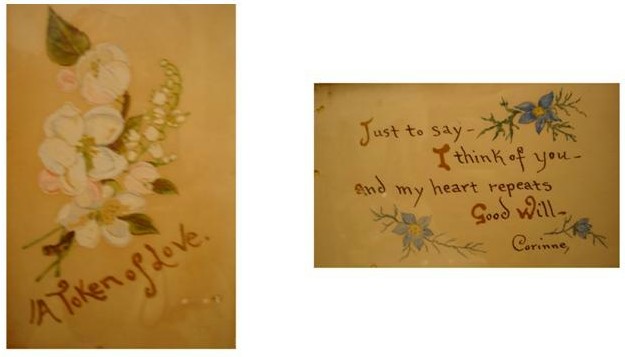

I remember her working on some of the pieces I was able to acquire. The greeting card below is such a piece. She created it and sent it to her friend who was in hospital at the time. The get well card was tied together with ribbon. Sally Moulder, knowing that I would treasure such a card passed it on to me when she discovered it in some old mail of a relative.

Get Well Card-5x7, Oil on paper, Corrine Houston, ~1948.

Flowers, 12x14, oil on canvas, Corrine Houston, ~1948.

Miss Corrine had a few wealthy friends who commissioned paintings for their homes. The two flower paintings below were done for a friend who had asked to do two flower paintings in a portrait format of a certain height. After Miss Corrine had produced and delivered the paintings, she was horrified when she saw that the lady had cut them to fit two antique frames she had in her collection, and, clearly, the frames were not suitable, at least for one of the pair.

I used this bit of information when purchasing the paintings years later in an auction. I would have paid whatever it took to buy the paintings, but in observing at least one other lady showing interest in the paintings, I commented, “These frames are really nice; I would love to have them, but someone surely didn't know how to choose a painting for them. After purchasing them for less than $100 each, the lady rushed over to me and said assuredly, “I will give you $200 for the paintings, and you keep the frames.” After seeing the ladies disappointment on my refusing her offer, I left the auction feeling a little bit guilty and a lot elated with my acquisition. No one could ever love these paintings as much as I do.

Flowers-Oil on canvas, 6x12, Corrine Houston, ~1948.

One of my favorites of her pieces is what I would call mixed media, though Miss Corrine would shutter at the notion. In cleaning out an upstairs closet in my grandparents home, my mother had come across a large photographic print on cardboard that had become so faded that it was no longer possible to see what was in the photograph. The picture must have been pushing a hundred years. My mother commented that it was an antique and shouldn't be tossed out, but that it was clearly not worth hanging, so what should we do with it? Then she asked, “Do you want to see if Miss Corrine can do anything with it?”

I couldn't wait to see what Miss Corrine would say about it. She took it in her lap and studied it for a long time, adjusting her glasses several times before commenting. Finally she looked at me and said “Davis, (that was how I was called then.) this is, oh my, this is magnificent. There is much to be seen in this photo so look at it, until you can tell me what you see here. If you are to be an artist, you must learn to see things even when they are very subtle”. I took it and looked closer. At first I saw nothing, almost a blank, yellowed, brown piece of cardboard that was obviously very old. Then suddenly I could see a haze and what might be a street in a village.

She began to point out things she saw in the picture. Some of them I could believe; others, I agreed just because she was so sure and I wanted to see. In fact, it still looked pretty much like a blank piece of paper to me. She took a brush into her hand and said, “I don't want to ruin a masterpiece so I will put just a touch of paint here and there to help the picture say louder what it is attempting to say. This became my first exposure to painting negative space. Like magic, the buildings in the scene emerged from the brown paper as she darkened the surrounding negative space. An almost transparent blue sky allowed the ancient board to peek through. A few white lines placed the figure of a person in the foreground. She was having a great time drawing meaning out of the paper. Putting very little paint on the board, she made it a color picture but left its monochrome appeal and allowed its age to remain with dignity. Finally, she said, “We must give it a name. What shall we call it? It is so mysterious.”

Then it came to her in a flash. “Vail of Mystery”. So she added the title onto the painting. She refused to sign her name to it, because it was someone else's work. “I just awakened it,” she said.

Vale of Mystery, 14x20, Corrine Houston Oil on a very old print

My mother was ecstatic when she saw the result. Many years later, when dividing mothers property, I came across the painting. No one had any idea what it was but it all came back so clear to me.

I worked on paper with pencils and chalk for about three months before graduating to oil. My first painting was done on cardboard.

Snow Scene, 8x10 oil on cardboard, Jim Trolinger, 1947.

Miss Corrine was not terribly happy with it. “You forgot what you learned about perspective.” I am afraid that she over estimated what I had learned. I had done the single point perspective exercises flawlessly, but had little idea what they meant in the broader sense.

It seemed, for years, that the paintings I liked best and the ones others liked best were uncorrelated. The painting I always rated as my best was the windmill in Holland. By this time I almost understood perspective.

Windmill, 12x16, oil on canvas, Jim Trolinger, 1949.

Bayou Scene, 8x10 oil on canvas, Jim Trolinger, 1948.

I think Miss Corrine's favorite was the Bayou scene. Sometimes I wish I could paint like this now. I think this painting may be one of those that Miss Corrine “touched up” a lot.

My first attempt at portraiture represents another one of those cases. I attempted to paint Roy Rogers and his horse Trigger. I was extremely frustrated by my inability to produce a portrait of Roy. Over and over I scraped off the face to Miss Corrine's dismay. Even after she “touched up” the face, I was unhappy. How could I do such a great job on his hat and still have him looking like a sad sack? I hated this painting. Mother, on the other hand loved it more than anything I had done. Another of my favorites was “Winter Scene II”, which I did next.

Roy Rogers, 12x16, Oil on Canvas, Jim Trolinger, 1949.

Winter Scene II, 8x10 Oil on canvas, Jim Trolinger, 1948.

I still remember some of the songs she sang with the guitar,

“Ain't she sweet?

See her walking down the street.

Now I ask you very confidentially,

ain't she sweet?

Oh me oh my……..”

I learned the meaning of some of the longer words like “ confidentially, impression and perfection” for the first time from that song.

She had about 10 students during the time I was taking art, none younger than Chiggy and I but a few much older. Miss Corrine would not let a painting leave her home that she didn't like, herself. She would “touch up” a painting for us, sometimes converting a disaster into a virtual “work of art”. It was not always clear with some paintings how much she did and how much the student did. Sometimes when I would get tired or frustrated with a painting I would say, “Miss Corrine, will you ‘touch up' my painting for me?” She quickly caught on to this ploy and “touched up” my painting only when she chose to do so.

I got along well with her most of the time, but I still remember every one of the times that I got in trouble. One day I was painting away on a painting called “The Birch Trees” The painting was looking really good and I was proud of it. One of my classmates, a pretty little girl, who lived even closer to Miss Corrine than I did, was leaving her lesson at about the time I arrived. She hung around for a while to flirt with me, and I was a lot more interested in impressing her than I was in painting. Clowning around with my painting, I took a big brush, dabbed a pile of black paint on it, and pretended to slap it on the painting. It seemed quite cute and funny, until a big chunk of the paint flew off the brush and landed right in the middle of my beautiful sky. Oh, was I ever in trouble.

Miss Corrine was bent out of shape when she saw what I had done. She worked for a long time “touching up” my painting. She somewhat rescued it by making the leaves of the birch trees black.

Miss Corrine had a few very strong opinions about art, and she was quick to state them. She had seen some of the new art, created by the abstract expressionists, and a few local teachers began to teach the new notion that students should paint whatever they feel and not attempt to learn skills from the teacher. She was outraged at this.

The Birch Trees, 12x16, oil on canvas, Jim Trolinger, 1948.

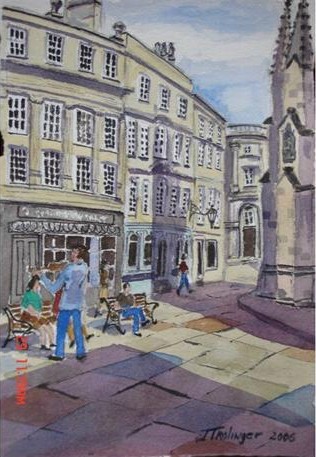

Bath, UK, 8x15, Watercolor on Paper, JimTrolinger, 2006.

One of her more quirky eccentricities had to do with certain colors. She refused to use the color orange, and she told us all to remove it from any art set that we might purchase. She believed that it was an unnatural color and had to be mixed. I avoided using Orange for most of my life until recently when I discovered how many great possibilities it provides. She would turn over in her grave if she saw one of my orange skies, a style I learned from artist, Tim Clark.

Miss Corrine taught us to make a point on the brush by rolling it between our lips, a practice that would really be frowned on these days when toxic substances are cause for panic. She told us the story of one of her parents' visitors exclaiming, “Corrine is eating paint!” An her father replied, “No, Corrine is just about to paint something very delicate and beautiful.”

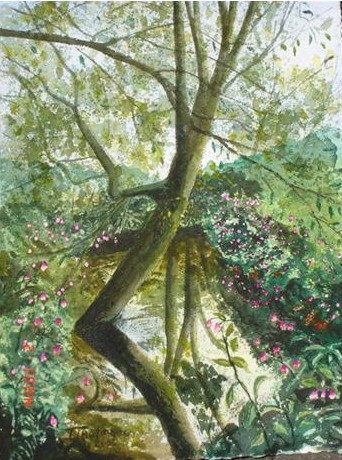

From that time on art was always a great escape for me even when my profession turned elsewhere. At times when I found myself really down, I could sit and paint, and all the cares seem to drift away. In this way, I turned out one or two paintings each year for the next twenty or thirty years. I always thought of Miss Corrine when I picked up a brush. Just in case she happens to read this, I include a couple of my most recent paintings. From experience, however, I imagine that the earlier ones would get a higher rating from the judges of the “America the Beautiful” contest.

One thing is for sure. I do finally understand perspective.

Flitwick Moor, UK no. 11, 8x15, Watercolor on paper, Jim Trolinger, 2006.